People’s Contribution

People’s Contribution to the Great Himalayan National Park

The story of the Great Himalayan National Park (GHNP) is not only one of biodiversity and natural beauty—it is also a story of people. The people’s contribution to the Great Himalayan National Park has been instrumental in both its creation and ongoing conservation. From traditional forest users to local leaders and eco-volunteers, the GHNP stands today as a World Heritage Site thanks to decades of community cooperation and stewardship.

Community Role in Forest Protection

For generations, the communities living in the Tirthan and Sainj valleys have respected their natural surroundings. These forest-dependent populations have traditionally relied on the GHNP landscape for grazing meadows, medicinal herbs, sacred groves, and water. Their sustainable practices, shaped by local customs and beliefs, laid the groundwork for the region’s conservation ethos.

Even during the establishment of GHNP, the locals played a crucial role. Rights settlements, eco-development committees, and later partnerships through BiodCS and local NGOs ensured that people were not just bystanders—but central participants in shaping conservation policy.

Dilaram Shabab’s Visionary Efforts

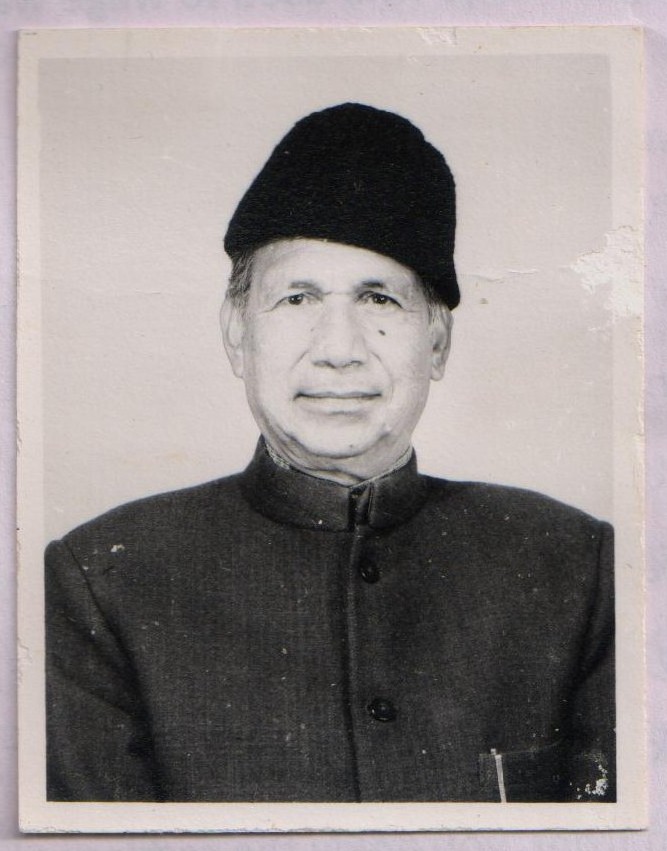

One of the strongest examples of people’s contribution to the Great Himalayan National Park comes from Shri Dilaram Shabab, an ex-MLA whose early advocacy in the 1970s helped initiate the park’s formal planning. His letters and public support led to political backing that ultimately resulted in GHNP’s official notification in 1984. Shabab’s idea was simple yet powerful: the mountains, forests, and wildlife of Himachal Pradesh belonged not just to the present but to future generations.

His words still echo in the park’s philosophy today: “The park should really be the people’s park, and not merely a source for outsiders to grab its natural resources.”

Sh Dilaram Shabab, ex-MLA (Click to enlarge)

UNESCO Recognition and the People’s Role

The official recognition of GHNP as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014 wouldn’t have been possible without grassroots involvement. When the IUCN team visited in 2012, it was the local villagers, gram panchayats, and deities’ worshippers who submitted a heartfelt memorandum, emphasizing their spiritual and ecological bond with the land. Their unified voice underscored the belief that GHNP was not just a conservation area—it was a living, breathing cultural landscape.

Conclusion

People’s contribution to the Great Himalayan National Park has shaped its identity and success. From the early days of advocacy and community engagement to current efforts in eco-tourism, biodiversity protection, and awareness campaigns, locals remain the backbone of GHNP’s conservation mission. As this unique park continues to thrive, it will do so hand in hand with the people who’ve called it home for centuries.

The letter continued, “We the people of Himachal Pradesh should also be proud of our magnetic mountain peaks, gigantic canyons, lush forests, mighty glaciers and valuable fauna and flora. Our beloved Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the great admirer of our natural assets, had rightly stressed that we should also maintain in our country this system, not only to meet today’s need but to anticipate those of tomorrow and put forward our plans and programs to expand the nation’s parks, recreation areas and open spaces, in a way that truly bring parks to the people’.

Dr Parmar had kindly set in motion the proposal for the creation of national parks in Himachal Pradesh. On the basis of the Survey Reports submitted by Dr. J Gaston, of the Canadian Wild Life Service and Dr Peter Garson of the World Pheasant Association, the government of India, initially decided in the year 1976, to establish Wild Life Park in Tirthan and Sainj Forest Ranges of Kullu District.

When Shri Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy, the then President of India, who was visiting Kullu-Manali sometime in June 1979, was a god-sent opportunity, with receptive mind for public good, he gave a patient hearing and assured to take up the park issue with the government, on his return to the capital.

The final notification, adding more area to the park and giving it a new name of the Great Himalayan National Park, was issued in March 1984. The park was selected as one of the first national Parks in India to demonstrate the approach of linking biodiversity conservation with local, social and economic development, broadly known as Eco-development. This concept is new both to the field staff and local people. Thus to make the approach viable, an alternative system more sustainable and remunerative for the local people has to be worked upon.

On declaration of the Great Himalayan National Park comprising the forest areas of Tirthan and Sainj Vallies, the forest department and the people of the local area protected the Bio-diversity value of the park, which in turn attracted the UNESCO towards the Park for its exceptional natural beauty and conservation of biological diversity.

To evaluate the suitability of the Park and its adjoining Conservation area, for inclusion in the list of “World Heritage Sites”, Dr Worboys, the Vice-Chairman, IUCN, visited the Park on Oct., 2012. On that occasion, local NGOs and stakeholders presented a memorandum on the working of GHNP that “We hail UNESCO, we are stakeholders, the park is not for sale, adding that the park should really be the people’s park and not merely a source for the outsider to grab its natural resources” to Dr Worboys.

Agreed upon the memorandum, on June 23, 2014, the Great Himalayan National Park was granted the World Heritage status, by the UNESCO. The Principal Secretary (Forests) came out with a statement, “the villagers will continue to enjoy their traditional rights and will be an integral part of the national heritage”. This was a welcome move on the part of the Forest Department to placate the sentiments of the stake holders who were kept back in the system.

Contribution of thousands of downtrodden village folks, forest dwellers, neighbouring communities, comprising 13 gram Panchayat of the Sainj and Tirthan Valley areas and thousands of devotees and worshippers of deities and Jognies, dotted from Tirath (Hanskund) to far off Rakti Sarovar, constitute the integral part of this World Heritage. “Extracts from Sh. Dilaram Shabab’s write-up on GHNP

As in the past, the Park authorities still depend a lot on the local contribution to the conservation of the Park and form the biggest spirit in the Management of the Park.